|

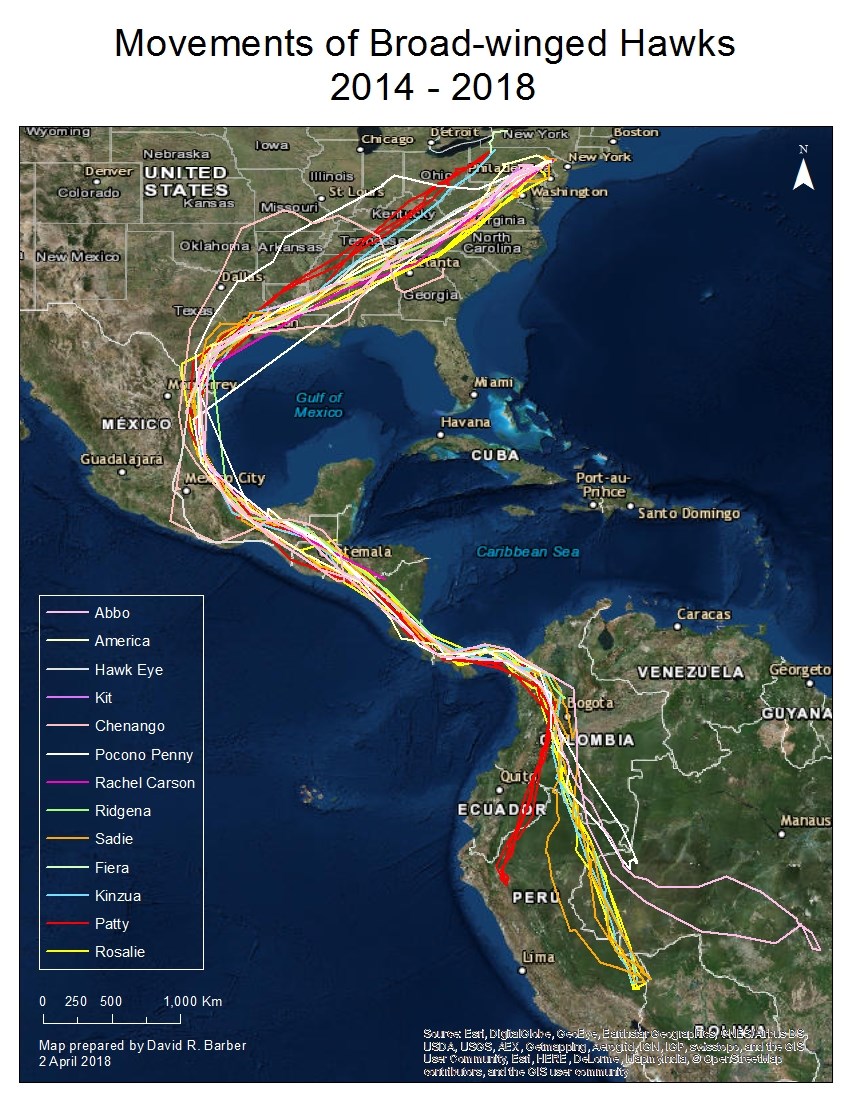

| Broadwing Hawk migration map, courtesy of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary |

For two weekends now we've ventured up to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, first with my sister and the second with my daughter and two grandkids. It struck me both times how often I return here and now, having just turned 60, it feels more like visiting with an old friend. We just pick up where we left off.

I first came here on a field trip in college with my landscape professor and small class of six students. We painted and sketched at the lookouts the first day, camped at Blue Rocks that evening, and worked in the forest the second day, interpreting the season and the land as we chose. My friend Steve and I returned a few times that year to explore the trails and paint some more. With the exception of the years I lived in South Carolina and Vermont, I've been back several times each year since.

The mountain and its surrounding landscape speaks to a complex relationship with humans. For the environmental historian, it may be easy to learn the history in some archives or database but ease does not reflect this complexity from the quiet of a library or reading room. Our work happens in the field where we can hear and see the histories from other-than-human perspectives. We incorporate these into our analysis and interpretation of the histories of sites and events.

|

| First spotter on the first day of the 2020 migration count. |

We hiked to the popular overlooks where first-timers gawk and catch their breath not realizing how much science is happening here. My sister and I watched the first hawk spotter of the season take his post on the North Lookout to begin the 2020 count. Four Broadwing Hawks for the first day. The following Saturday with my daughter and kids, we scrambled out to the edge of summit carefully picking our way between boulders to find a sitting spot away from a building crowd of birders and hikers.. Seventeen Broadwing Hawks were counted by the time we settled in for a mid-morning snack. Mid-August and the Broad-Winged migration is on! In a few weeks the daily count will top a hundred a day flying over this summit, while other raptor species will join in their southern stream out of Pennsylvania, the Northeast, New England and Canada.

|

| Laura climbing the stone steps to the North Lookout. |

The fall migration of raptors in Pennsylvania is legendary and at Hawk Mountain particularly so. Tied to this annual months-long event is a solid scientific research program that has helped explain this phenomenon and the role people have played in it. Targeted research on the Broadwing Hawk in particular has revealed how this secretive forest hawk has endured human pressures on its forest habitat, how far they travel to their wintering grounds (GPS trackers), and the status of populations over time. Scientific research combines with conservation seamlessly here and this is not lost on hikers who absorb the information on interpretive panels and study count charts at major trail intersections.

|

| Valley and Ridge Province of the Appalachian Range. |

Hawk migration is just such good scientific storytelling and with data so readily available and robust, the plot only gets more exciting as the story unfolds. We hiked down along the flank of the mountain through Ice Age relic fields of freeze-thaw shattered Tuscarora sandstone, metamorphosed river bed sediments thrust upwards in several mountain-building events that spanned 450 million years. At many of the overlooks and throughout the rock fields, we observed the fossilized trackways of Arthrophycus, a worm-like arthropod, a sand dweller of river banks, mouths of estuaries, and boundaries of sea and shore.

|

| Fossil trackways and burrows. |

What is the relationship between Broadwing Hawks, we wondered, and this mile-long rock field? Looking up into the forest canopy we observed that the predominate tree species here is Chestnut Oak, a tough, muscular tree of the Northeast mountain forest. It was near an open plain of shattered sandstone that the first Broadwing Hawk to be GPS tagged ( named Rosalie - how cool is that, conservation historians?) was caught at her nest in a Chestnut Oak. Chestnut Oaks grow in challenging, rocky terrain, their roots spreading laterally as well as deeply into the crevices and fractures between the rocks. These oaks knit the whole scene together above and under ground and provide stable and mature habitat for forest-dwelling hawks and the small mammals and snakes they prey upon.

|

| Aiden with massive Chestnut Oaks behind and up slope, anchoring the rock field. |

When we see the big picture from a vantage point, Chestnut Oak forest cloaks the mountain in deep green and spreads like an ocean down slopes, into coves, and out across the Northeast Appalachian range. The forest offers wildlife continuous habitat for 60 miles along the Kittatinny Ridge. Hawk Mountain is one section of this long mountain and it is easy to see why Broadwings nest in these woods and are positioned along this major migration route. As GPS tracking has demonstrated, Broadwing Hawks are might migrators who follow a route that stretches from Pennsylvania to the mountain forests of Ecuador and Peru. The nesting range of Broadwing Hawks in Pennsylvania aligns with the expansive forests nearly completely recovered after restoration efforts became a priority in the Commonwealth in the 1920s. Their nesting range is expanding northward as forests reclaim landscapes once heavily farmed, quarried, and logged into New England and Canada.

|

| Chestnut Oak forest dominates the mountain ridges and rocky valley. |

Tuscarora Sandstone is the primary rock type we encounter at Hawk Mountain and dominates the summits and slopes of South-Central and Northeast mountains of the Ridge and Valley Province of Pennsylvania. Outcrops of vertical formations are iconic to many popular mountain summits while road cuts along Pennsylvania highways exhibit everything from horizontal beds to twisted and tortured bends that make it appear almost fluid. There are many places to see "rivers of rocks" including Hickory Run State Park which is next on my list of places to go. A visit to the aptly named Hawk Falls is in order during migration season. You can also camp at the edge of a rock field at Blue Rocks just six miles down the mountain from the sanctuary.

|

| A good workout! |

From the perspective of the rock fields, the mountain is still wearing away. We heard a few small shifts out on the rock field as the sun heated the boulders up to the point they were hot to the touch. Heat and cold are part of the process of fracturing. From the perspective of the oaks, the rock fields are excellent places to anchor a forest to a mountain. From the point of view of the Broadwings, the Chestnut Oaks are the best places to build a nest and raise young. Rosalie has nested here for many years now, raising four chicks successfully. She'll be off for Peru soon to winter in the mountain forests there and that's what knits our conservation story to the southern hemisphere. n increase in logging and land clearances are growing threats to winter habitat for Broadwings and the research done at Hawk Mountain has a clear international conservation potential.

|

| Love our raptors! Goofball sister. |

The spectacle of hawk migration season connects us to rocks and trees and rivers of wind. These are stories I love to investigate time after time, now with grandkids in tow. Like an old friend, the mountain and its stories welcome us back throughout the seasons, and for the environmental historian each climb and ramble adds to the unfolding and complex history of our relationship to the mountain and birds of prey.

Notes:

Fact Sheet on Broadwing Hawk conservation and science at Hawk Mountain: https://www.hawkmountain.org/raptors/broad-winged-hawk

No comments:

Post a Comment